The Investment of a Classical Christian Education

By Peahi Kapepa, TCS parent

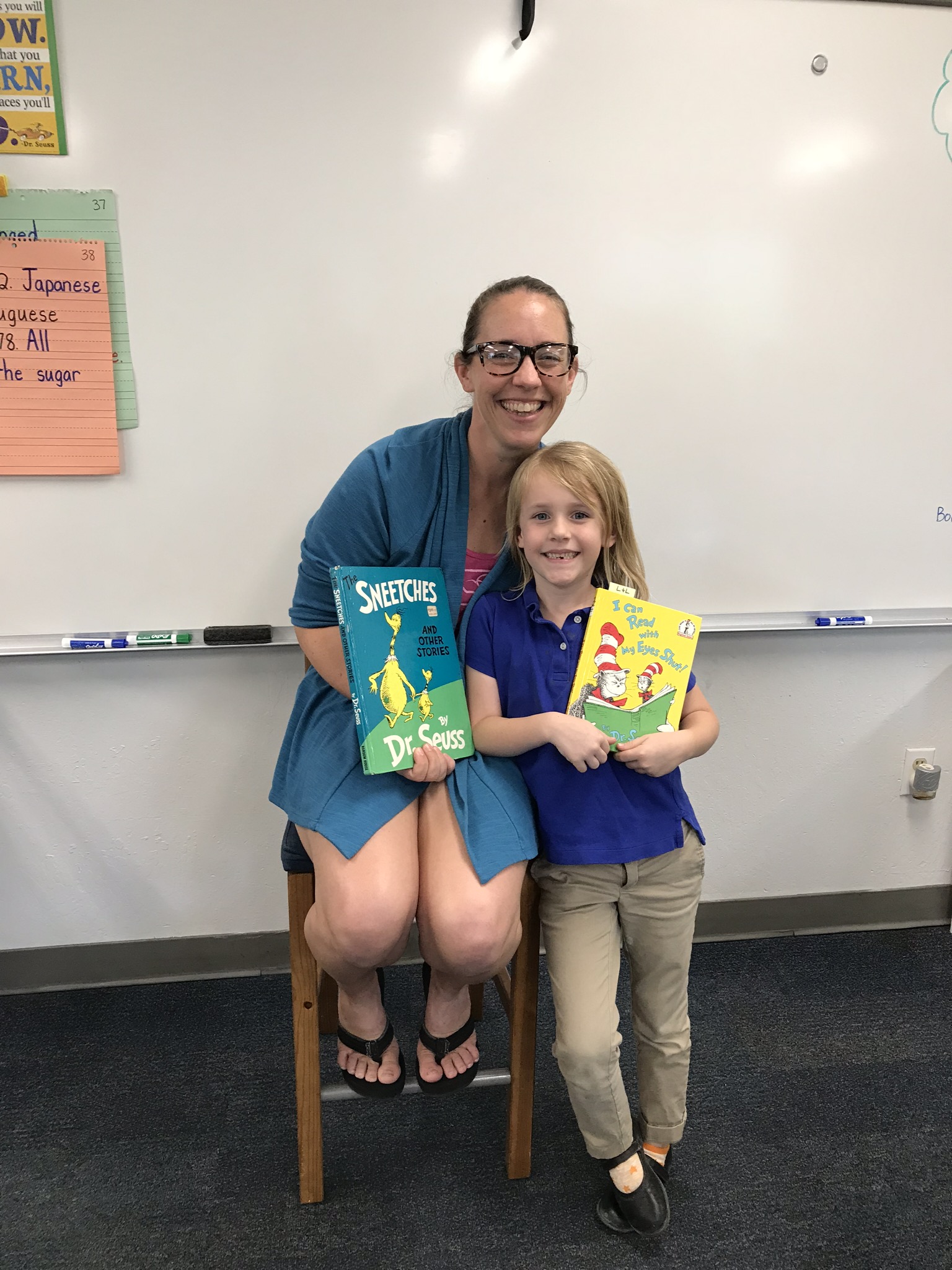

When deciding to send my daughter to Trinity Christian School, I was very attracted to the school as a whole. First, for the obvious reasons that the Bible is taught and prayer and Christ are woven throughout everything the students do from playtime to resolving conflicts and problems.

Now, three years later, I’ve learned about the Classical Christian approach and its benefits as a natural progression of education. At first, it sounded strange to me. When it comes to things that seem complicated and fancy, I assume that it’s something that it’s not. My skepticism was proven right and wrong. Right, by learning what Classical Christian education is, I realized it is relatively simple and a common-sense approach that has been shown over time. And wrong, in that the American public education system has strayed far from what was working for so long. The “new” progressive method has “dumbed down” the basics of how children are taught.

The Trivium is comprised of Grammar, Logic and Rhetoric stages but I’ve chosen to focus on the first part of the Trivium: Grammar. Not only is grammar taught but heavily emphasized in the classical format in K-6. Grammar is explained using the vehicles of song and chant which is invaluable to memorization. It’s also fun and causes the kids to thrive in their early years. Instead of merely learning “grammar,” students are learning all subjects from a logical perspective. It has been fascinating to see this at work in my daughter.

Another part of the grammar stage of the classical method that attracted me to Trinity is the focus on language. I was glad to find out that Hawaiian is taught in the first few years of Elementary school because my daughter and I are part-Hawaiian. I have taught her to first identify herself as a child of God, but it’s important to me that she learn about her culture and the beautiful place we are blessed to live.

The other language subject that impressed me is that Latin is taught. My parents both studied Latin in high school and college, and I know how much they value the understanding it gave them. I look forward to my daughter delving into the subject.

We are approaching our fourth year at Trinity, and I am absolutely sold on the classical Christian method of education. I’ve had the perspective of witnessing the school as a parent and as a teacher. I will testify to the value of classical Christian education and how my daughter has blossomed and excelled in this system. Our Christian family values are being reinforced at school. My daughter is receiving a superior education based on a proven record. It will continue to enhance her life after she graduates.

Making Music in Classical Christian Education

Written by Claire Butin, Elementary Music Teacher

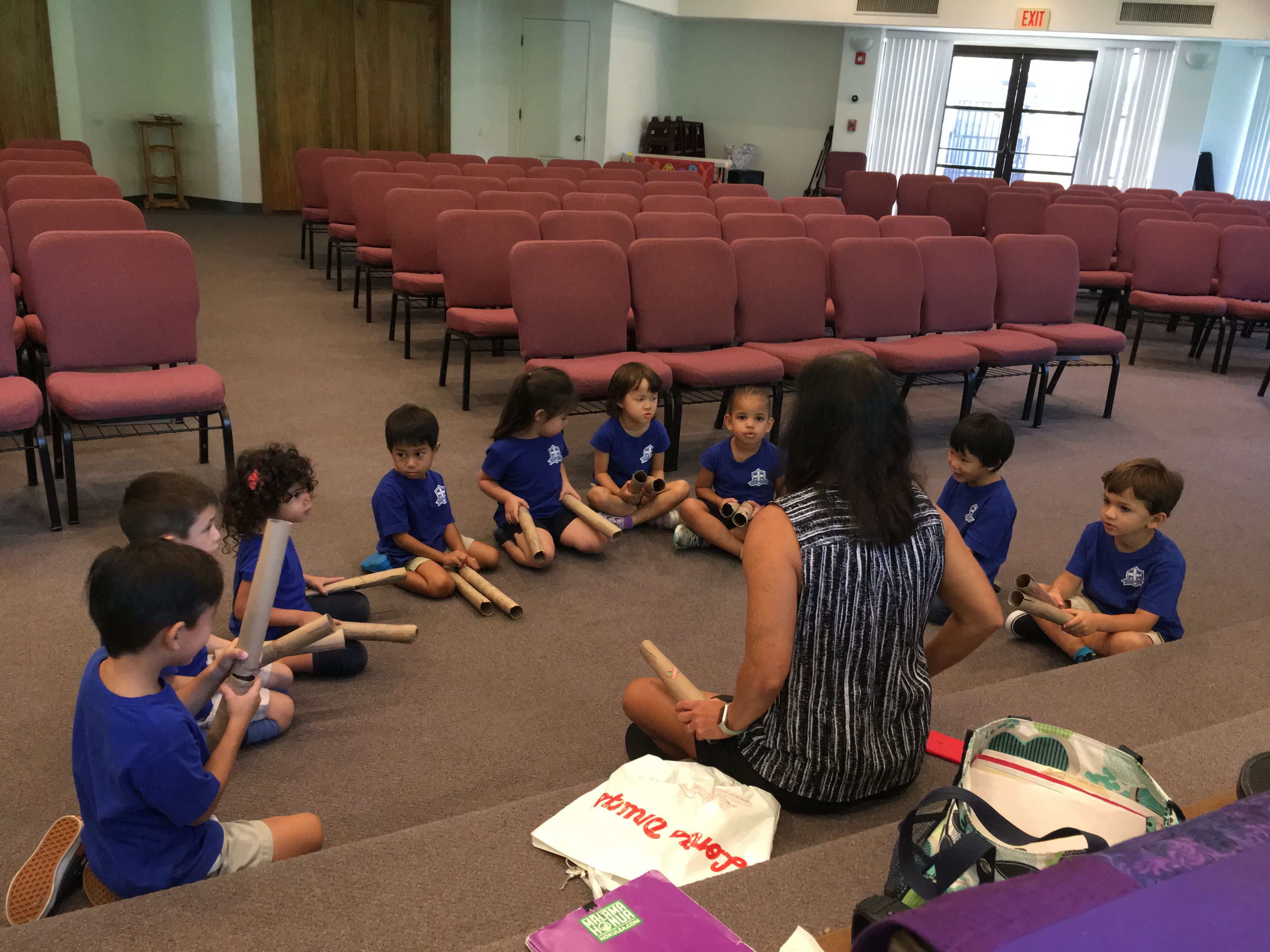

Music is a powerful learning tool in classical education. In the grammar stage, students learn how to use their God-given voices in the very best way, the basics of music theory, the beginning stages of music reading and instrumental performance, and an appreciation for many classical masterpieces of music. Music can bring joy and change hearts, and it is important to give each child this gift.

In kindergarten and first grade, we learn to sing with solfege and solfege hand signs for the different scale degrees. The hand signals help the students get the feeling of the notes into their bodies and to firmly establish pitch relationships. These hand signs are internationally used.

Instrumental performance is an important part of music education. Even at a young age, children are developing self-control, teamwork, rhythm reading, stage presence, musical expression, and having fun through playing simple percussion instruments such as rhythm sticks and maracas.

The elements of music are also taught in a classical way: through songs and jingles!

Each month, the students study a different composer. Though Vivaldi did not write any words for his masterpiece, “The Four Seasons,” we have added a few. By having the children sing these classic melodies with some added words, it helps them remember the composer, which part of the piece they are listening to, and what mood the composer was trying to convey.

Body percussion is a fun way to have students grasp harder rhythmic concepts.

Finding the Difference between the IB Program and Classical Christian Education: Part 4

Finding the Difference Part 4: On the Classics & the Gospel

Written by Mark Brians, 7th & 10th Grade Humanities Teacher

(This is the final installation in a series of four essays, click here for part one, and here and here, for parts two, and three, respectively).

Where do we find our definitions?

In his masterful work on virtue, philosopher Alasdair McIntyre has explained how we “can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’”

In much of this discussion about the major differences which distinguish the classical Christian tradition from other modes of education (the IB Program in particular), we have highlighted how these differences come from differences of definition: what it means to be human, what the purpose of education is, and how to measure excellence. These definitions are, in some sense, like answers to the question above, “what am I to do?” The answers and definitions furnished by classical Christian pedagogy, which we have discussed, are born from a prior answer to a more fundamental question, “of what story or stories are we a part?”

To this question we offer a simple answer: we are a part of the Gospel story —God’s story. But God’s story is a large one, including within it, many smaller stories. In being a part of the Gospel story, we find ourselves inextricably inheritors of another story, the classical one (hence the term for our pedagogy, “classical Christian education”). In this final essay, we will examine what exactly we mean by this, and why this matters for school life.

What do we mean by “Classics” and “Christian”?

What do we mean by “Classics” and “Christian”?

By “Christian” we refer to the Person of Jesus Christ as He is faithfully revealed in scripture. By this we refer, concomitantly, to the life and witness of the people of God in history and across the globe; and to the work of the Spirit of God in and through His Church.

By “classical” we refer to the collective wisdom and experience of the human past in general, with a particular focus on those of the West and Hawaii. This includes but is not limited to the histories, and names, and songs, and genealogies, and thoughts, and stories, and scientific discoveries, and skills, and practices, and knowledge, and moral lessons, and failed attempts at glory, and great victories; the living and dying of those people who came before us and gave us the now which we inherit by nature of being alive. We are the inheritors of a world that existed before we did, in the Gospel we are commissioned to be a part of the story God gave it.

Why does this matter for school life?

This may seem strange in an era that is deeply suspicious of words like “tradition” or “authority” and where the prevailing attitude in literature, philosophy, and history studies is purely critical (as opposed to receptive, attentive, grateful).

The problem, however with our culture’s deep resentment of authority and the past, is that it creates a vacuum in which nothing is called true except for inert “fact.” Roger Lundin incisively reveals what happens to a culture in the absence of these greater common authorities: “Instead of appealing to an authority outside of ourselves, we can only seek to marshal our rhetorical abilities to wage the political battles necessary to protect our preferences and to prohibit expressions of preference that threaten or annoy us.”

The observations of Clark and Jain is that “all education takes place in a context of a mythos (story), a logos (reason), and practices. Without a commitment to a tradition that establishes these, education is a drift from its moorings… and technological solutions alone will only protect us for a time.” Rather than balk against the notion of authority beyond the myopic present, we acknowledge, in the words of Michael Polanyi, that “no human mind can function without accepting authority, custom, and tradition: it must rely on them for the mere use of language.”

The classical Christian model of education begins its course by building a “robust and poetic moral education” grounded in the Gospel of Jesus and the wisdom of the classical tradition before moving to analysis or critique. This does not only help us to “get the facts” but enables us to array them within a life-giving framework by which we can work cooperatively, creatively and rationally towards critical thinking and thoughtful exploration. Instead of seeing the witness of history or the authority of the Gospel as foreclosures on human discovery, an ugly “gulf to be bridged,” we celebrate them as “the supportive ground of process in which the present is rooted.”

So far from eschewing the analytical, or “higher order”, categories of student performance, this bedrock, laid in the richness of the human past (“the classical”) under the genius of the Gospel (the Christian), actually produce the kind of vibrant academic community so many educators and families long for.

The Gospel is light, and in that Light, we see the light. Only within the fecundity of a historical witness and the Gospel that offers an authority beyond individual urges does reason truly flourish. As Gustav Mahler said, “Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.”

Why Speech and Debate Matters: Part 4

Why Speech and Debate Matters: Part 4

Written by Rachel Leong, Class of 2016

Ralph Waldo Emerson once said,

“Speech is power, speech is to persuade, to convert, to compel.”

I was terrified to take Speech and Debate. My heart leapt out of my chest, my knees would shake, and my palms would perspire every time I thought about it. A required class that involved arguing competitively? No thank you. Politics? That scares me. Waltzing around in suits in Hawai’i humidity? Hello, stress sweat.

However, once I got past my first tournament in Junior Varsity (JV) Policy discussing economic engagement with Cuba and medical tourism, I realized professional arguing was not as terrifying as I thought it would be. A few laughs here and there from not understanding political terms and pretending like I did made the process not only educational, but lighthearted and fun. From that memorable first round saying, “It’s for the children” multiple times in my concluding speech, I grew and was massively pushed out of my comfort zone all the way to the state tournament in JV Policy in my sophomore year of high school. After one year in debate, I tried my hand at the speech side of the forensics world and fell in love.

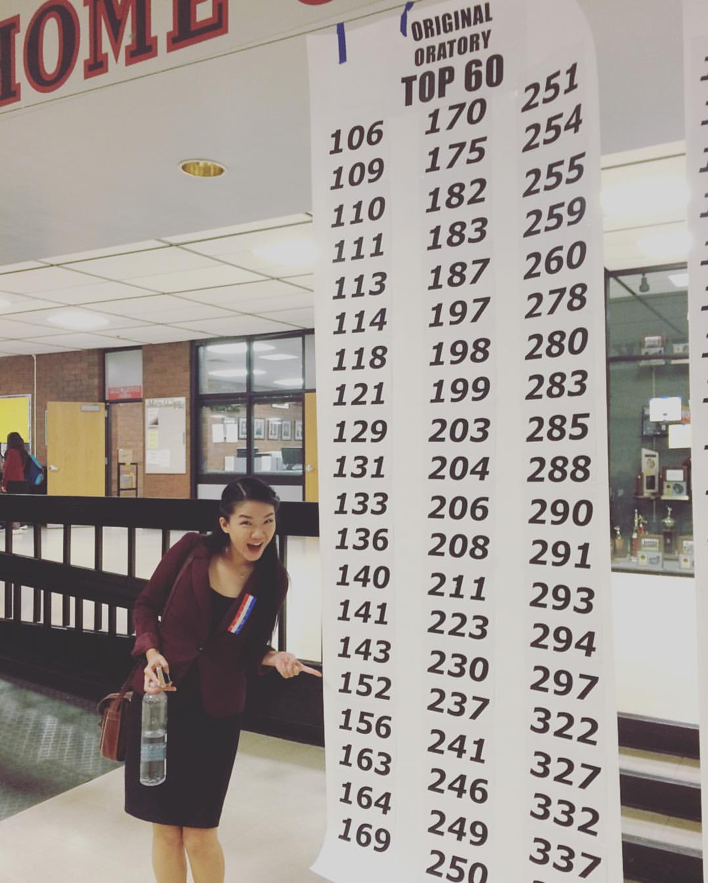

I competed in Dramatic Interpretation (DI), Humorous Interpretation (HI), Duo Interpretation (DUO), and Original Oratory (OO). These categories allowed me to play writer, director, choreographer, and actress all in one, with all the creative liberties I could dream of. Speeches ranged from acting out “Bridge to Terabithia” (DUO), to a consolidated version of my senior thesis (OO), to my Nationally-successful piece discussing “Society’s Lack of Authenticity and Fear of Vulnerability” (OO). I felt like I could convey whatever message I wanted to, in the exact way I wanted to. I could curate a piece that was mine.

Needless to say, I was completely hooked for my last two years in high school.

When I became immersed in speech, my aim was to put my entire heart into every single tournament and get that trophy. As the tournaments progressed, I was met with a different reason than success. My coach discussed with me how I was representing not just the school, but the morals and values of a Christian in a secular league. The way I was competing was not the traditional way to succeed in the NSDA, but regardless, I was doing well. I chose to refine skill, content, and wit rather than falling prey to the flash, crass, and cliché that was so easy to win with. I refrained from using any profanity or crude language in a category that thrives on that for success. This shocked multitudes of people who knew that Humorous Interpretation was not a category for many who proclaimed to be Christians. And through God’s will, I won the State title and competed in Nationals with a completely clean piece. Getting that far did not make logical sense. This was when I knew I was a part of something that was out of my control. I began to understand that my skills and abilities brought me to a platform where my role was larger than just little ole’ me.

While my knees still shook and my palms still sweat, I knew that the Lord would speak through however I performed. Terror became a trust in an understanding that this was what I was supposed to say, to this audience, at this moment. Junior year, I won 1st place in Humorous Interpretation, qualified for Nationals and 4th in Dramatic Interpretation. My senior year, I won 2nd in Original Oratory, qualified for Nationals, 3rd in Duo Interpretation and the District Student of the Year Award. While these titles can seem impressive, from the beginning I had learned that nothing I achieved was due to my own abilities. God was using my achievements as a platform for His light and His love.

"I began to understand that my skills and abilities brought me to a platform where my role was larger than just little ole’ me."

It was all for one goal. To embody, speak, and live out the values of Jesus in an otherwise obsessive, achievement-driven world—to speak truth in love (Eph. 4:15). Specifically, in Original Oratory, I found the Lord using me as a vessel for His truth. I worked hard, yes, but I knew that I had to do what He was leading me to do. I made it to the Top 60 in the nation in Oratory. Why? I wholeheartedly believe it is because the people in each of my rounds, leading up to that final room, needed to hear the words the Lord spoke through my mouth.

Fast forward to being a college sophomore, and I am no longer competing in Speech and Debate. Currently I am studying Organizational Communication, minoring in Sociology, and working as an Educational Programs Intern in the Intercultural Life Department, advocating for justice in faith, specifically in areas of racial reconciliation. I invested myself in these areas after seeing the empowerment of young leaders in the NSDA. These were world changers, 16- and 17- year olds, who were starting organizations advocating for women of color, those differently-abled, women in STEM fields, men not fitting the societal masculine mold, the hurt, the oppressed, the poor, the people God calls Christians to intentionally work on loving well. I garnered a heart for the marginalized and oppressed after the Lord “broke my heart for what broke His,” to speak out and remind followers of Christ that loving others does not mean avoidance of the hard and uncomfortable.

"I wholeheartedly believe it is because the people in each of my rounds,

leading up to that final room, needed to hear the words

the Lord spoke through my mouth."

On a daily basis, I use the skills I learned during my time in speech and debate for almost everything. Every speech I give with ease, every controversial conversation I think through cautiously and have the confidence to discuss it came from the long nights of drilling facts into my head, memorization and after-school meetings. Debate gave me the mindset and critical thinking to thoroughly examine life issues, instead of blindly believing everything I hear. Speech gave me a voice to speak out and stand for what I believe in. I would not, I repeat, would not be in this position if I did not have the confidence and tools Speech and Debate gave me.

Just like the characters in The Wizard of Oz, I feel like I gained a heart, brain, courage, and a home. Speech and Debate was by far one of my most favorite memories in high school, and equipped me best for taking on the world.

I will always be an advocate for the values and experience that speech and debate cultivates in students, and I believe that every high schooler will reap more than they realize. Everything that I have accomplished, every plaque, every trophy, every ballot—I attribute it all the Creator who has formed me exactly in this way for the purposes of furthering His Kingdom. His instilling of passions and abilities is only using me as a vessel and testament to His goodness.

“Now to him who is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to his power that is at work within us, to him be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations, for ever and ever! Amen.” —Ephesians 3:20-21

A Class of 2016 alumna, Rachel Leong attended Trinity starting in 2008. Now in her second year at George Fox University, Rachel is an Organizational Communications major and Sociology minor. In the future, she hopes to possibly start a Christian non-profit or get her PhD in anticipation of being a Professor in Intercultural Studies (and own a dachshund).

Finding the Difference between Classical Christian Education and the IB Program: Part 3

Part 3: On Excellence

Written by Mark Brians, 7th and 10th Grade Humanities Teacher

This is part three in a series of four, click here for part one, and here for part two. In a previous article, I discussed one of the major convictions which distinguishes the classical Christian model of education from a host of other kinds, namely the International Baccalaureate Programs. Here, I countenance a second major difference in the classical Christian model: our understanding of the nature of educational excellence. Much like the question we asked in the earlier essay concerning the nature of humanity, it might be easy to assume that “we all know what we are talking about, when we use the word excellence”. The truth, however, is that excellence, by its very nature, is a relative term. The qualities that make one an excellent banker are very different from those that make one an excellent bank-robber. The nature of excellence is beholden to the subject it modifies. So then, two schools might both employ the word “excellence” in describing their programs of study (or other similar words, such as “superior” or “robust”) while differing greatly in the nature of the education they provide.

What does excellence look like in the classical Christian Tradition?

What does excellence look like in the classical Christian Tradition?

As discussed in the earlier essays, the classical Christian model is very clear on the kind of education we want to provide: namely, the formation of humans whose loves are ordered to the glory of God and in service of their neighbors; humans whose formation in the liberal arts [1] will prepare them well for a wide array of skills [2] in the project of peace and human flourishing. The idea of educational “excellence” refers uniquely to specific articulations of educational goodness and the concomitant pedagogy respective to each. Thus, our standards of excellence countenance the content, the instructional practices, and the kinds of school culture which best serves this goal. McLuhan’s dictum, as regards to practices, holds weight: the medium is the message.[3] We cannot dislocate the “what” of education from the “how” of doing it. Everything —from content, to student ratios, to faculty and administrative practices, to modes of assessment— is a part of the education. How does this differ in practice from more common forms of education? To demonstrate it might be helpful to examine three (of many) practical examples of the way in which the classical conviction is enfleshed, or lived-out, in practice.

1. Multum non multa

This Latin proverb translates loosely to “much not many”. We place a high value on developing mastery and depth of thought over merely giving students a cursory perusal of many variegated subjects. Let us borrow the language of “uncoverage” pioneered by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe to describe this kind of pedagogy.[4] Often we find, when institutions grow focused on “covering” vast amounts of content, they have successfully “covered” (i.e. hidden, veiled, withheld)[5] much of the meaning; creating a vacuous pedagogy of impersonal facts whose meaning is equal only to their extrinsic market utility. The classical Christian model instead dares to suggest that when students learn deeper, they actually learn more. As studies in history and mathematics reveal, it is this kind of deep learning, of conceptual mastery and intellectual wonder, that best teaches for retention and breaks the detrimental pattern of cram-pass-forget.[6]

2. Difficult does not necessarily mean Good

It is easy to assume, when faced with the current plight of American education (the apparent lack of “excellence”), especially when compared with that of emerging countries, that if the answer is not “more” then it must be “harder”. If American students, the thinking seems to go, are falling behind, then we must push them farther and harder. And so we pride ourselves when we brag about the “rigor” or “difficulty” of our classes and schools. Often, however, a failing system is symptomatic of a much deeper sickness. Merely running an ailing body harder and faster, whipping “rigor” into it, exhausts an already over-taxed system. The cudgel is no remedy for the sick. This is the danger of making sheer difficulty our measure of excellence. Instead, the classical model takes a holistic approach to the human learner, understanding the place for both rigor and rest in education.

.jpg) 3. Excellence and Mensurability

3. Excellence and Mensurability

At other times, “excellence” can simply refer to scores on standardized tests or college acceptance rates. While we certainly see the real value of such metric assessments of academic vitality, we feel that these by themselves are not adequate to measure the kind of excellence for which we aim. Helpful as they may be, they are understood by educators within the classical tradition as part of a much larger system of measurements by which we evaluate learning outcomes. For if the purpose of our education is the formation of affective creatures along lines of virtue and mutual flourishing —if this is our standard for excellence— then many other things in addition to raw test scores must be taken into account. We must be careful not to limit excellence to mere success on tests which, for all their worth, are unable to give an account of a student’s honesty, or courage, or oratory skills, or poetic genius, or musical skill, or deep retention of content. In all our desire to provide an excellent education for our children, we must be wise about the kind of excellence to which we refer. The promise of sheer “excellence alone” does not guarantee that the education a child receives is one that aims their loves towards a holistic, Gospel-centered, vision of human flourishing.

Endnotes

[1] The classical seven (Music, Geometry, Grammar, Logic, Rhetoric, Arithmetic, Astronomy) crowned by Philosophy and Theology.

[2] In this distinction we follow the historical distinction between “arts” (i.e. ways-of-being-human, ways-of-relating-to-the-world-and-to-others) and “skills” (i.e. the utilization of things, ex. robotics, graphic design, commerce, etc.).

[3] McLuhan, Marshall. 1994. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge: MIT Press.

[4] Wiggins, G. and Jay McTighe. 2005. Understanding by Design, 2nd Edition. Alexandria: ASCD Press.

[5] See the discussion in Calder, L. 2006. “Uncoverage: Toward a Signature Pedagogy for the History Survey.” The Journal of American History. pp. 1358-1370.

[6] See Mays, J. 2017. “Slaying the Cram-Pass-Forget Dragon.” SCL Summer Conference Presentation. (notes available here

Explaining Classical Education Succinctly: What Will Your Elevator Speech Be?

Explaining Classical Education Succinctly: What Will Your Elevator Speech Be?

A while ago, a friend asked me, “What is a classical education in 50 words or less?” He wanted a start on his own “elevator speech” to share with his friends and colleagues who expressed interest in the educational alternative he and his wife chose for their children. I’ve read, heard, written and spoken on this subject hundred of times. Most of the statements are lengthy, and the subject deserves the more lengthy treatments contained in books and pamphlets by luminaries such as Dr. Christopher Perrin, Kevin Clark and Ravi Jane, Douglas Wilson, Gregg Strawbridge, Dr. George Grant and many other contemporary reformers. But trimming it to 50 words! After four iterations while wrestling with the 50-word maximum here is my reply. Try it.

Classical education is pedagogy in the Western tradition about becoming fully human through the liberal arts, humanities, and gymnasium. It inculcates grammar, ancient and modern language and literature, reasoning and the art of persuasion, mathematics, sciences, arts, and physicality. It is the acquisition of truth, goodness, and beauty.

Rodney J. Marshall, Ed.D.

Head of School

Recent Posts

Tag Cloud

5th grade academics administration all school all-school alumni athletics big island blog christian christmas class of 2018 classical classical christian classical christian education classical-christian-education classical-education college commencement community coram deo debate discipline donation drama educatio education educational philosophy electives elementary exhibition faculty fine art golf tournament graduates graduation hawaii hawaiian history head of school IB program kaiulani kupuna day leadership makahiki may day missions music office outreach parentsArchives

Looking for more? Read our Grand Tour blog and Athletics blog!